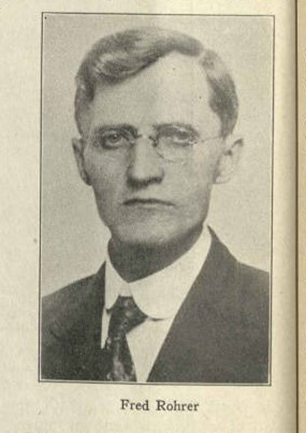

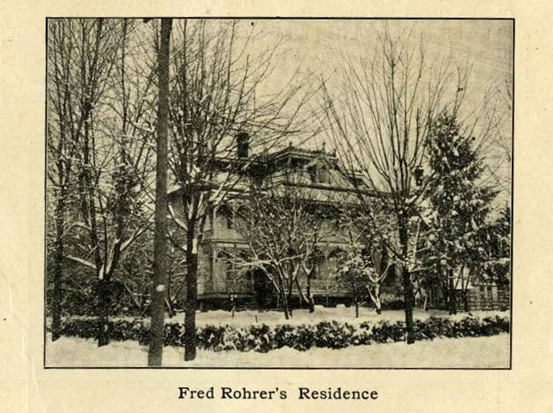

Fred Rohrer, unknown date, located in the Thirtieth Anniversary Souvenir Edition of the Witness,1926, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

Fred Rohrer, unknown date, located in the Thirtieth Anniversary Souvenir Edition of the Witness,1926, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

On December 24, 1903, an article from a Kentucky-based newspaper known as

The Bee

highlighted the following: “Not daunted by the fact that his house was blown up by dynamite, by being assaulted twice and severely beaten, nor by an attempt to made to lynch him, Fred Rohrer, editor of the

Berne Witness

, declares that he will continue his relentless war upon the saloon element of the town.”

[1]

That year had proved to be a defining moment for both Rohrer and the City of Berne. With the help of the

Berne Witness

, Rohrer tied Berne to the Temperance Movement, and helped put Indiana on the national map to Prohibition.

Religion and the Rise of Temperance

In the early nineteenth century, Indiana and other states across the Midwest saw the arrival of Mennonites, who traveled from northeast Switzerland, and Germany. Their religious beliefs stemmed from the Anabaptist Movement of the sixteenth century and encompassed a range of practices, such as “believer’s baptism, the separation of church and state, personal nonviolence, a rejection of church hierarchy and the refusal to take an oath.”

[2]

A range of societal changes influenced their exodus from the homeland, such as the Napoleonic Wars, poor harvests, and mandatory military service. As more Mennonite families experienced a world of religious and social freedom on America’s frontier, extended kin soon followed.

[3]

The network of chain migration resulted in the creation of small, German speaking settlements across the Midwest landscape, as Swiss Mennonites made the U.S. their new home.

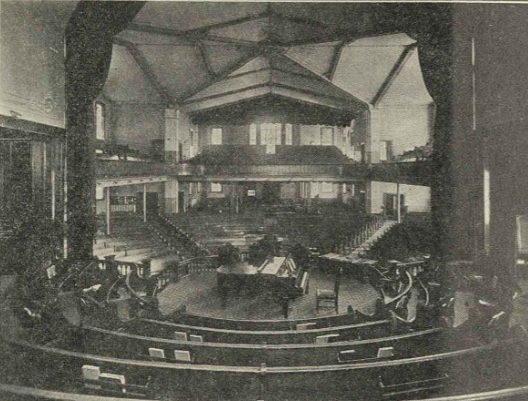

Interior of Mennonite Church in Berne, courtesy of the Thirtieth Anniversary Souvenir Edition of the Witness,1926, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

Interior of Mennonite Church in Berne, courtesy of the Thirtieth Anniversary Souvenir Edition of the Witness,1926, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

This was the case for sixteen-year-old Fred Rohrer, who emigrated from Berne, Switzerland to Sonneberg, Ohio, in the spring in 1883 with his parents and thirteen siblings. Three years later, the Rohrer family made their way to the newly incorporated town of Berne, Indiana, named after their original hometown. They arrived at a pivotal time in the town’s history. Rumblings of the Temperance Movement gripped the city leaders within the freshly established city, as the Mennonite population dealt with Berne’s growth. Historian John Eicher explains that during the late nineteenth century, the Temperance Movement began to influence religious and political identities of the United States and inspired the many secular organizations to link alcohol consumption to moral and economic problems that faced the U.S. landscape.

[4]

Methodist groups served as the bedrock of early temperance activism, and soon more religious groups followed, with the first major temperance group in Indiana appearing in 1826 with the formation of the American Temperance Society. However, it was not until 1828 that activism surrounding temperance intensified in Indiana.

[5]

Between 1830 and 1850, temperance organizers helped pass nearly 125 laws throughout the state that bolstered temperance by regulating liquor prices and amount sold.

Eicher explains that beliefs of piety, self-restraint, and morality connected Mennonites to the Temperance Movement. Drunkenness coincided with sex work and gambling ? all sins originating in the saloon.

[6]

Rohrer was quick to join the fight against liquor consumption. After purchasing an old Washington hand press and equipment from the

Decatur Press

and

Decatur Democrat

offices, Rohrer established the

Berne Witness

in 1896, publishing its first issue on September 3. Recognized as a Temperance paper, the

Berne Witness

began as a weekly newspaper that by the turn of the century had a circulation of about 700. At the time, the city had a population of approximately 1,037 individuals.

[7]

That same year, Rohrer incorporated a supplement to the

Witness

in the German language, reflecting the steady growth of the Mennonite population.? Berne’s status as a respected Hoosier town was emerging ? but in 1902, the discovery of oil just a few miles outside of Berne’s city limits threatened the population’s solitude. Transient single, working-class male workers, alongside prominent oil men seeking a fortune, flooded the local population. As a result, concerns over vice-related activities, like drinking, gambling, and sex work, skyrocketed.

[8]

Many prominent leaders believed this was the perfect opportunity to enforce liquor laws before the town became any bigger.

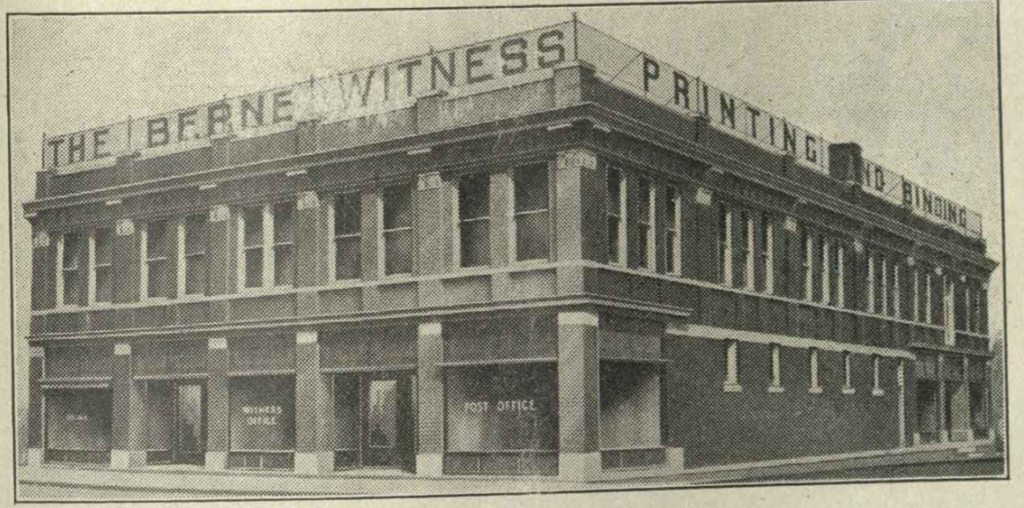

Image courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

Image courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

As a leading supporter of Prohibition, as well as an active voice within the Christian Temperance Society of Berne (CTSB), Rohrer’s role in establishing the city as a dry town is highlighted in the

Berne Witness

. Tales of his protests, his success and failures, and his dedication to upholding his religious beliefs are spread across nearly twenty years of publications. His influence in the CTSB allowed Rohrer to use his paper to establish a fluid connection between Temperance activists and the larger community. Rohrer and the

Witness

played a crucial role in turning Berne into a dry town. It frequently reported updates on local Women’s Christian Temperance Union’s meetings, alongside changes in Indiana’s liquor laws and liquor license requirements. More importantly, the

Berne Witness

became a weapon that enabled Rohrer to call out local authorities and saloon owners for their illegal activities. As his paper grew in popularity and readership, Rohrer became a local legend ? but his fame also made himself the main target for retaliation.

Rohrer’s Fight

In September of 1902, Rohrer met with several other men met to discuss the “enforcement of the local option provision” brought on by the Nicholson Law.

[9]

The law required a two-year waiting period between liquor license applications and its issuance. Additionally, the law allowed for remonstrances ? or public votes and petitions ? for the denial of any liquor license.

[10]

The CTSB was quick to form petitions against every saloon in Berne. Rohrer, also a member of Indiana’s Anti-Saloon League, commented on the remonstrance’s in the

Witness

in 1902, saying that Christian patriotic forces in Indiana were attempting to solve the saloon question by eradicating saloons all together. “The saloon must go,” he wrote, “Remonstrances have been circulated and a great majority of the names of voters have been secured.”

[11]

Initially, these remonstrances were successful. The

Witness

reported on December 5 that two saloons ? one owned by Jacob Brennaman and the other by Jacob Hunsicker ? officially closed, with another to cease in March of 1903.

[12]

However, the celebration of these closures did not come without complaint from others. Though the

Berne Witness

gave him unfettered access to disseminating his opinion, it also opened the door to immense retaliation by saloon owners and liquor drinkers. And, by the start of the new year of 1903, tensions escalated between saloon owners and Rohrer. ?Early in January, Rohrer posted a notice on the front page of the

Witness

, incentivizing the community to report liquor violations and sign their public petitions:

Opponents to the remonstrance often said that there would be more liquor sold in Berne if licenses were refused than if said license were granted. To assist in demonstrating the matter, $100.00 has been deposited with the undersigned to be used as follows: $10.00 to be paid for the first, $15.00 for the second, and $25.00 for the third conviction of any one party by the Adams Circuit County. Money to be paid by the undersigned to such parties that file the complaint.

[13]

Monetary incentives, however, failed and remonstrances were ignored. The board of commissioners approved liquor licenses for several men across town, directly violating the Nicholson Law. The CTSB complained but were forced to take their grievances to the circuit court.

[14]

Rohrer spent the summer of 1903 biking ten miles to Decatur daily to bring Berne locals remonstrances to the circuit court. As early as March, the

Decatur Democrat

reported on Fred Rohrer’s appearance in Decatur on “temperance and saloon business.”

[15]

On June 4, the

Democrat

claimed that the City of Berne, despite protests, was still “wet,” as the commissioners court granted a license to John Reineker to operate a saloon in town. Rohrer’s remonstrance against Reineker had been declared insufficient due to his lack of attorney.

[16]

A month later, the

Democrat

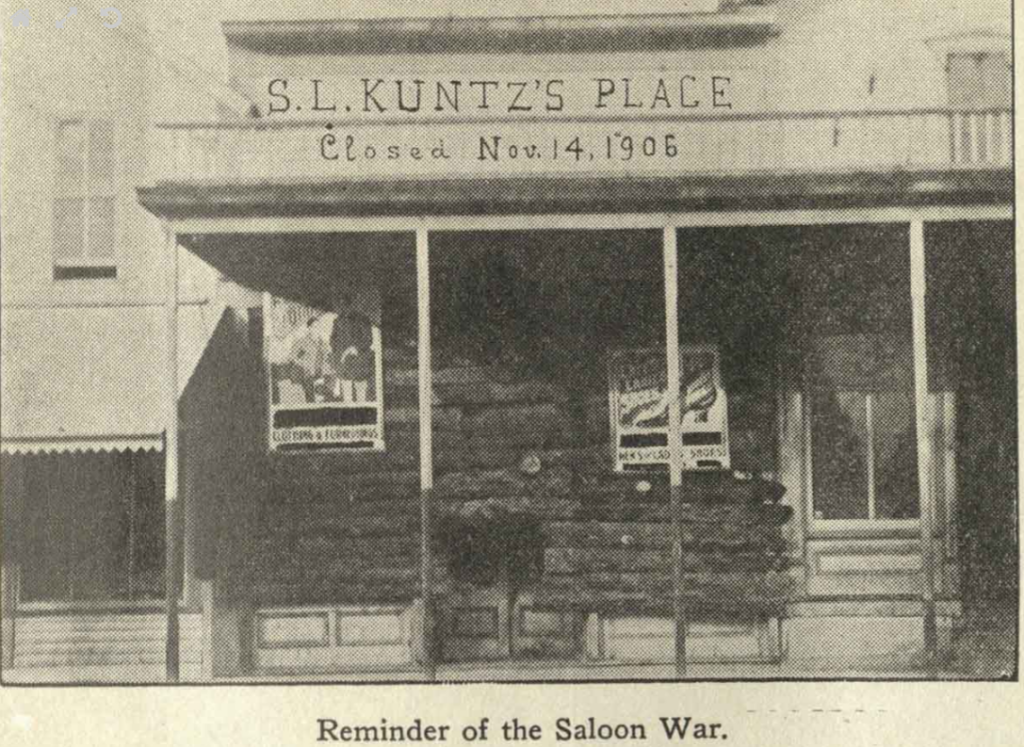

claimed that Rohrer was still busy in the auditor’s office, where he filed remonstrances containing 396 local signatures “against the granting of license to sell liquors to J. M. Ersham, William Sheets and Sammuel L. Kuntz.”

[17]

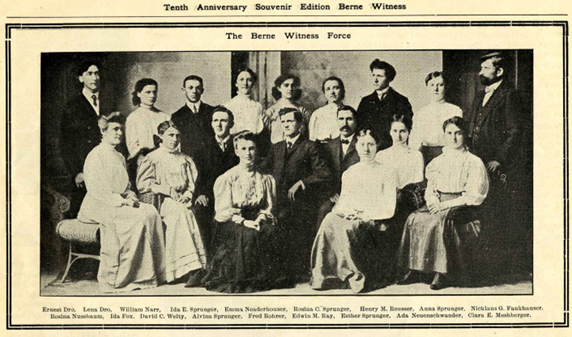

Berne Witness staff,1906, courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

Berne Witness staff,1906, courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

Tensions between Rohrer, Berne’s saloon owners and local anti-Temperance supporters peaked by September. After midnight on September 10

th

, Rohrer’s wife, Emma, awoke to a scratching noise coming from the first floor of the house. After investigating and finding nothing out of the ordinary, she returned to bed. Twenty minutes later, Rohrer awoke to two heavy explosions in his home. As Rohrer and his family slept on the second floor, someone slipped one stick of dynamite through a downstairs window and another under his front porch. The explosions destroyed half of his home. Rohrer described the wreckage in the

Berne Witness

a few days later:

We looked out the windows in the kitchen and dining room and then came into the sitting room, just beneath the bed room we were all sleeping in. The moon was shining in through a large hole in the wall where the front door used to be, and through two other large holes where windows were missing. A few shreds of the curtains left hanging from the top were wafted in by the south wind and made a spectral noise and together with the debris of broken pieces of glass and dishes and furniture lying topsy-turvy gave the room a ghastly appearance.

[18]

Local carpenters were quick to get to work on repairing Rohrer’s home the following morning. News of the attack spread across the Midwest, with articles regarding the murder attempt appearing in the

Indianapolis News

, the

Kentucky Post

, and even the

Salt Lake Herald

.

[19]

But many, especially Rohrer, were not surprised. He wrote in the

Berne Witness

, “As had been stated in Friday’s issue and in other papers, the attack was not unexpected to us…Every night as we went to bed last week I told my wife to be prepared for almost anything.”

[20]

It was later reported that the special grand jury tasked with investigating the incident failed to bring any indictments in the case, and no one was charged.

[21]

Rohrer’s home, courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

Rohrer’s home, courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed

Indiana Memory

.

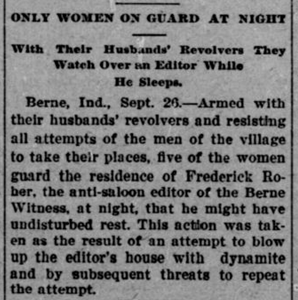

Women within the CTSB began surveilling Rohrer’s home shortly after the attack.

The Plymouth Tribune

reported that five women, armed with their husbands’ revolvers, kept guard to ensure that Rohrer could rest peacefully. In fact, their continued support encouraged him to move forward. On September 11, the morning after the bombing, Rohrer biked back to Decatur to approach the commissioners’ court with a remonstrance against Joseph Hocker, a Monroe resident who was seeking to apply for a liquor license in Berne. The

Berne Witness

stated that Rohrer also brought thirty-three cases of law violations to a grand jury against Berne saloonkeepers, claiming that the attack on his house was “very naturally connected” with the saloon fight in town. A grand jury convened and handed down six indictments and saloonkeepers had to pay a minimum fine, As a result, on November 18, sixty suspected patrons of Berne’s saloons received subpoenas to appear before the court to testify.

[22]

“Only Women Guard at Night,” The Plymouth Tribune, October 1, 1903, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

“Only Women Guard at Night,” The Plymouth Tribune, October 1, 1903, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles.

Enraged by the indictment, a mob against Rohrer formed on November 19. Resident Louis Sprunger approached Rohrer in the

Berne Witness

offices, challenging him to a fight out on the street, which Rohrer refused. Later that evening, Sprunger followed him into the post office, and Sprunger attacked him. Two female workers came to Rohrer’s defense, tackling Sprunger and forcing the man to leave. After retreating to the safety of the

Witness

offices, the president of the town council, Abe Boegly, attempted to drag Rohrer out but failed to get him on the street. Instead, Boegly decided to give Rohrer a “beating” until the local marshal arrived at the scene to break up the fight. As Rohrer was taken to safety, a mob ? consisting of saloonkeepers and other locals ? gathered outside of the

Witness

offices to determine the extent of Boegly’s assault.

[23]

The Indianapolis News

covered the incident and stated that Rohrer was advised by the local sheriff to temporarily leave Berne out of fear of more violence. He found asylum in Decatur, where he released a statement that he “proposes to continue the fight against the saloon until his enemies kill him.” Rohrer did not return home until a week later, and on December 4, the

Kansas Prohibitionist

reported that Rohrer began arming his home and offices with revolvers and shotguns. His wife, who refused to leave her husband’s side, began practicing with the weapons to protect the home. The increased violence in the town, however, forced saloonkeepers to come to a compromise with Rohrer and the CTSB. On December 18, the

Berne Witness

reported that John Reineke, J. M. Ehrsam and Samuel L. Kuntz offered a compromise ? the saloonkeepers would go out of business on April 1 of 1904, provided they were dismissed on paying the costs of their current indictment charges.

[24]

Image courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed Indiana Memory.

Image courtesy of the Tenth anniversary souvenir edition: The Berne Witness, accessed Indiana Memory.

As concessions were deliberated, Rohrer released another statement on Christmas Eve, declaring that he would not concede despite his friends fearing that he would be murdered. It was clear that Rohrer would not back down, no matter how much violence saloonkeepers and liquor supporters inflicted on him. On December 29, the

Indianapolis Journal

reported that “after one of the bitterest anti-saloon battles in the history of the State,” saloon owners Reineke, Ehrsam, and Kuntz agreed to close their doors on the grounds that within a few days Rohrer would drop his cases against the men regarding various liquor violations.

[25]

As the City of Berne approached the new year, it seemed that the liquor fight was finally coming a peaceful end.

Moving Forward ? Rohrer’s Legacy

Ultimately, 1903 proved to be the most defining year for Rohrer’s activism and for the City of Berne. Over the next three years, Rohrer and the

Witness

reported the continued forced closures of Berne’s saloons and liquor law violators. However, the election of

Governor James Franklin Hanly

? a staunch supporter of Prohibition ? in 1904 brought an end to the violence that accompanied Rohrer’s fight. Governor Hanly’s involvement in the Temperance Movement solidified the ban of alcohol at the highest political level with the Moore Amendment, which enacted a county option law regarding the ban of alcoholic beverages.

[26]

The liquor fight officially ended in 1907, when the city rejoiced over the last quantities of alcohol being carried into the street and drained. Berne was officially a dry town and remained that way until the repeal of the 18

th

Amendment in 1932.

[27]

* The Berne Witness?will soon be digitized and incorporated into the Library of Congress’s?

Chronicling America

?database and IHB’s own?

Hoosier State Chronicles

, to give historians the chance to explore Hoosier grassroots efforts within the Temperance Movement and Prohibition.

Notes:

[1]

“Indiana Editor, Takes His Life in His Hands,”

The Bee

, December 24, 1903, accessed

Newspapers.com.

[2]

John Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty’ Piety, Politics, and Temperance in Berne, Indiana, 1886 ? 1907,”

Indiana Magazine of History

107, no. 1 (2011):? 4, accessed

https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/12591/18853

.

[3]

? Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 5.

[4]

Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 10.

[5]

Charles E. Canup, “The Temperance Movement in Indiana,”

Indiana Magazine of History

, 16 no. 1 (1920): 13, accessed

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27785940

.

[6]

Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 11-13.

[7]

U.S. Census Bureau, “Indiana City/Town Census Counts, 1900 to 2020,” City and Town Census Counts: STATS Indiana, accessed https://www.stats.indiana.edu/population/PopTotals/historic_counts_cities.asp. According to the 2020 Census, the population of Berne is just above 4,000 people.

[8]

Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 2;?Learn more about the connection between vice and industrialization with

our post

about the effects of the Gas Boom in Muncie, Indiana.

[9]

Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 21; In 1895, the Nicholson Law was passed in Indiana. This law states that the majority of voters in townships and cities can halt the approval for liquor licenses issued to any applicant. See the Indiana Historical Society’s

Temperance and Prohibition Time Line

for more information on Indiana legislation regarding Temperance.

[10]

Jane Hedeen, “The Road to Prohibition,” Indiana Historical Society, 2011, p. 3, accessed

1d7d71dfbb39529a736fdba5279a5ba9.pdf (indianahistory.org)

.

[11]

“War on Saloons,”

The Berne Witness

, November 11, 1902; In this context, a “remonstrance” refers to a forceful protest, expression of complaint, or formal statement of grievance.

[12]

“The Liquor Fight,”

The Berne Witness

, December 5, 1902; “War on Saloons,”

The Berne Witness

, November 11, 1902.

[13]

“Liquor Being Sold Illegally in Berne?,”

The Berne Witness

, January 20, 1903; For reference, $100.00 is equivalent to about $3,549.23 today.

[14]

Eicher, “’Our Christan Duty,’” 24.

[15]

Decatur Democrat

, March, 5, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

.

[16]

Decatur Democrat

, June 4, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

.

[17]

Decatur Democrat

, July 9, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

.

[18]

“God Saved,”

The Berne Witness,

September 15, 1903.

[19]

“Two Explosions Under Residence,”

The Indianapolis News

, September 10, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

; “Dynamited,”

The Kentucky Post

, September 11, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

; “Dynamite Outrage,”

The Salt Lake Herald

, September 11, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

.

[20]

“God Saved,”

The Berne Witness

, September 15, 1903.

[21]

“Failed to Indict,”

Daily News-Democrat

, September 30, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

.

[22]

“Only Women Guard at Night,”

The Plymouth Tribune

, October 1, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

; “F. Rohrer’s Home Dynamited,”

The Berne Witness

, September 11, 1903; Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 26.

[23]

“Editor Rohrer Brutally Assaulted,”

The Berne Witness

, November 20, 1903.

[24]

“Editor Rohrer in Peril from Mob at Berne,”

The Indianapolis News

, November 19, 1903, accessed

Hoosier State Chronicles

; “Fred Rohrer Again,”

The Kansas Prohibitionist

, December 4, 1903, accessed

Newspapers.com

; “Saloon Keepers Offer Terms,”

The Berne Witness

, December 18, 1903.

[25]

“Indiana Editor, Takes His Life in His Hands,”

The Bee

, December 24, 1903, accessed

Newspapers.com

; “Editor Fred Rohrer Wins a Long Fight,”

The Indianapolis Journal

, December 29, 1903, accessed

Newspapers.com

.

[26]

Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 28; Stacey Nicholas, “J. Frank Hanly,”

Digital Encyclopedia of Indianapolis

, accessed

J. Frank Hanly – indyencyclopedia.org

.

[27]

Eicher, “’Our Christian Duty,’” 17, 29.